The FinOps Foundation justifies its relevance by pointing to persistent cloud waste—often cited in the ~20–30% range, with some surveys reporting that many organizations believe waste can reach 40%+. It also places a heavy emphasis on “cloud spend” (often more than long-term profitability), while defining FinOps broadly as an operational framework and cultural practice that aims to maximize business value and create financial accountability via collaboration across engineering, finance, and business teams.

But this “FinOps force” has serious issues. And it’s not only about selling to an unsophisticated audience—it also fails a basic critical analysis.

Core problems with the FinOps framing

1) The preposterous separation of “usage” and “cost”

The biggest flawed assumption is that cloud usage decisions (made by software engineers) can be cleanly separated from cloud cost management (delegated to a specialized FinOps team). Any decision necessarily has costs attached. If you don’t explicitly model cost inside your architecture decisions, you’re implicitly assuming an infinite budget.

2) A deeper philosophical contradiction

If you dig into the “unique philosophy,” you run into an even stranger implication: that software engineering is cognitively harder than “FinOps,” so FinOps can be executed by less capable people. That’s not a serious foundation for an operating model.

Because of that, using “FinOps” as a label becomes counterproductive: it’s ambiguous, all-encompassing, and—by design—promises more than anyone can reliably deliver.

Recommendation: avoid the term FinOps and use more precise language—e.g., Cloud Financial Management.

There is nothing “special” about cloud spend

There’s also nothing uniquely magical about computing that demands a special culture or special team category. Cloud is a spend category like others.

A simple analogy: healthcare spend is also complex, distributed, and consequence-laden. Doctors don’t “provision EC2,” but they do choose among many treatments with different effectiveness/cost trade-offs. The key point is the same: the decision-maker must understand the trade-offs; you can’t outsource the thinking.

Cloud Spend Waste

Yes, cloud waste is real. Depending on the source, estimates commonly sit around ~20–30%, and some survey responses claim waste can be 40%+ in many organizations.

But “waste exists” is not a unique justification for a grand, all-purpose FinOps movement. Waste at scale exists everywhere. For example, a widely repeated estimate is that about one-third of the world’s food is thrown away. Planes also regularly fly with empty seats.

And in business, time is usually more valuable than the cloud waste you incur by taking productive shortcuts. The priority should be to grow revenues faster than costs.

Also: don’t confuse efficiency with effectiveness. Reducing waste is fine, but in a complex world you often have to experiment, and you don’t know the “final target” upfront—so optimizing for perfect efficiency too early can be the wrong objective. A common way to express this distinction is that efficiency is about minimizing wasted inputs, while effectiveness is about achieving the intended outcome.

Unsophisticated Audience Deceptions

The credibility of the FinOps Foundation is significantly undermined by repeated patterns of marketing that look like fraud or deceit—often amplified by sponsors/partners targeting an unsophisticated audience.

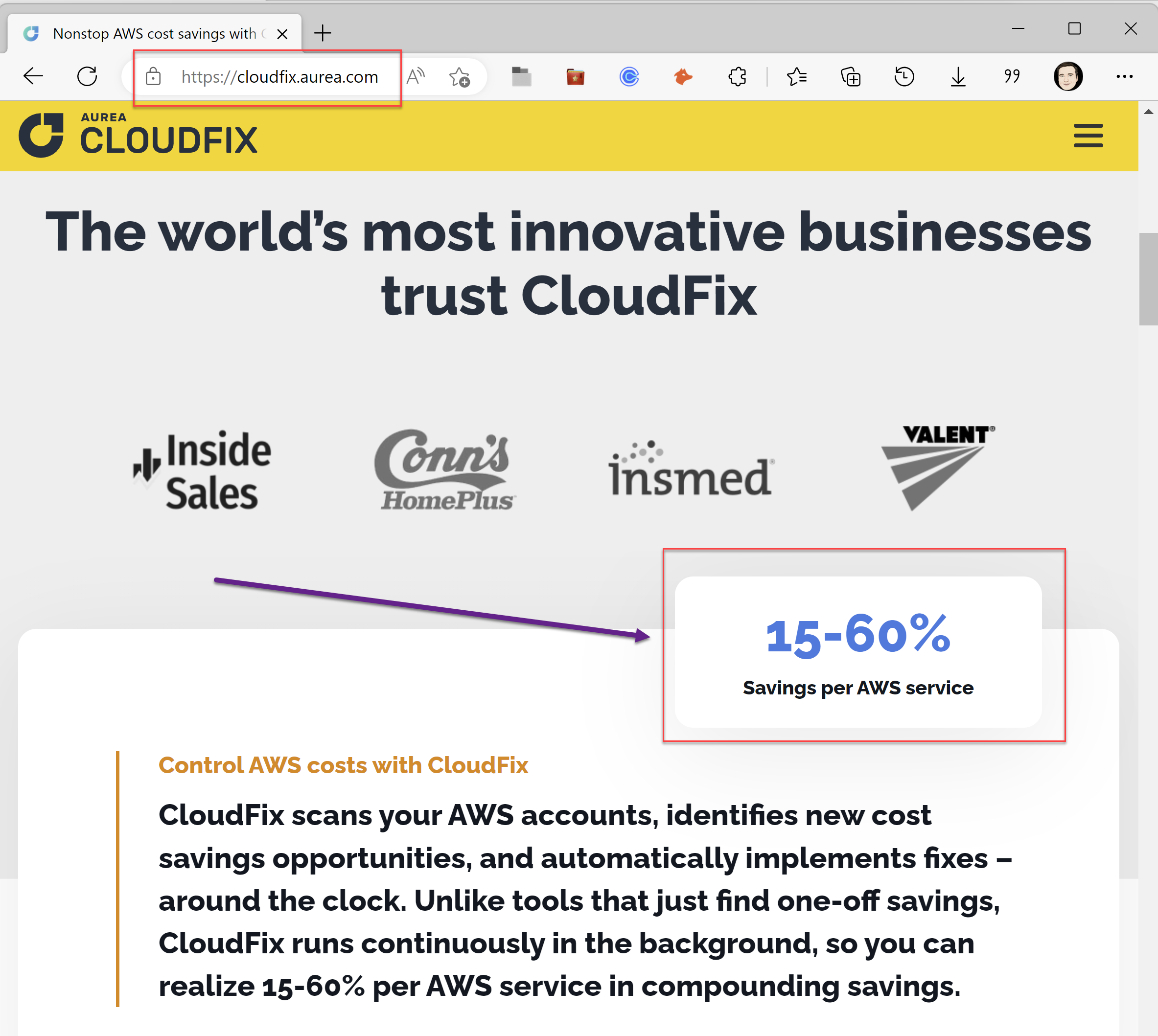

One example: CloudFix (marketed as a FinOps Foundation Premier Partner and associated with the ecosystem) promotes the idea that it can deliver “15–60% savings per AWS service”—positioned as broadly applicable, regardless of how optimized you already are. That claim is extraordinary, and the burden of proof should be equally extraordinary

This kind of messaging is comparable (in spirit) to famous advertising claims that were challenged as misleading—like litigation around “Red Bull gives you wings,” which resulted in a large settlement over allegedly deceptive marketing.

A related (and very practical) example of misaligned incentives: some sponsors still push AWS Reserved Instances over Savings Plans, even though AWS itself explicitly recommends Savings Plans over Reserved Instances due to flexibility and comparable discounts.

The real problem with public cloud: lack of cloud knowledge

The FinOps Foundation and/or its sponsors often imply it’s acceptable to run unoptimized architectures—because “it’s hard to keep up,” so you shouldn’t try; instead, buy software that will “solve” it for you.

That approach is false.

There is no hidden “FinOps magic” that software engineers cannot learn. And there is no substitute for becoming (and remaining) a productive cloud architect: you must continuously keep up with cloud developments—including the financial dimension. Cloud Financial Management is part of cloud architecture competence, not an optional bolt-on.